Repairer

- jenparkhill

- Sep 23, 2018

- 13 min read

By Jennifer Parkhill

Edited by Jenni Quilter

Repairer

On a single bed, seven bodies are arranged in a tangle.

The scene looks more like a litter of puppies than an orgy: the bodies are not quite flesh-toned, but an embryonic pink, the pink of underexposure to the world. They are completely hairless. Some mouths are agape; some touch lips. Heads hang locked around the crook of another’s neck. It is difficult to tell where one body ends and another begins.

Louise Bourgeois’s 2001 sculpture, Seven in Bed, captures the base, animalistic urgency we humans have for one another so precisely that it almost hurts to look at it. These bodies reach for each other without even knowing what it is that they want. Their desire is so fierce that it verges upon cannibalistic—they are unashamedly hungry. They are willing to devour one another in order to become stronger, to grow full. Though genitalia is visible, the bodies seem asexual, as if they’re feeding from a mother buried somewhere beneath them rather than on each other. In this sense, even though they physically appear to be adults, they more closely resemble newborns, consumed by emotion, as yet unaware of a culture that would require them to deny their dependence upon one another.

*

Monday morning. I awaken sweaty and puffy eyed, deeply disturbed by a nightmare in which my mother has died. A freak accident. A fluke. Something careless. She called for help and I couldn’t get to her quickly enough. It happened in her car. My stepfather didn’t answer the phone in time. The circumstances of her death made no sense, but the knowledge that I was unable to stop it from happening, that there was nothing I could do to reverse what had occurred, remained.

It doesn’t take a psychoanalyst to recognize that all of this fear stems from the fact that I am new to New York City and living a great distance from my mother for the first time in my life. I cannot jump to reach her, should she need me.

*

We spent ten difficult years together, my mother, my brother, and I. I held my mother’s hand, endured the sound of her sobs as she showered after work at the local diner each evening. I sat in the car while she attended her Alcoholics and Narcotics Anonymous meetings. I even offered to babysit people’s children at those meetings so that I could stay close enough for her to reach me, so that I could keep on eye on her, make sure she hadn’t slipped, that she wouldn’t trip over an unforeseen pothole and disappear down some dark street. For the five years before she entered recovery, I had wondered every morning if today would be the day that I would lose her to an overdose, to suicide, to harm by a junkie. I waited every night for that call. I told myself that she was already dead so that I wouldn’t be trapped in this limbo any longer.

When she finally found sobriety, she was resurrected, and I did everything in my power to make certain that I never lost her again.

My mother got me a job at the restaurant where she worked. We worked side by side every night, carpooled to work, stole moments in the silverware closet to share a sent-back steak. I cooked our meals, cleaned our home. We pooled our money and took turns driving my brother to school. I became her shrink, her partner, her supporter. When she remarried a few years ago, I helped her into her dress, did her makeup, styled her hair, and drove with her to the ceremony. I felt that I should have been the one to walk her down the aisle, but based on gender alone, the duty of giving her away was given to my brother. He and I both cried as he pushed her, very gently, into the new—but loving—arms of her groom.

I am infinitely proud of my mother; at times I am not sure who raised whom, who birthed

whom. Moving to New York City, away from her, was one of the hardest things I have ever done. For there is no shaking the feeling that even with her over fifteen years of sobriety, if I am not there to protect her from life’s troubles, some unexpected obstacle could shake her so violently that she will fall again. And so I dream. All the fears I shove away during the day come out at night.

*

Monday morning. I am sitting in a lecture, half-listening to what the professor is telling me about art, bits of information drifting in through a haze of old nightmares. I am browsing the internet for Louise Bourgeois. I have seen a documentary about her. I know that I am supposed to write about her. I click on a thumbnail of The Woven Child, enlarge it, and the lecture hall fades away completely.

This 2002 work by Bourgeois features a woman’s fleshy, pale-pink torso—headless, armless, legless—with a baby resting on her belly. The woman appears to be stitched together from patches of heavy cloth. The stitches are large and tight; they look surgical. She is nude. Her breasts, also made of cloth, are full, with nipples made from slightly darker fabric. The infant that rests on her belly is also flesh-tones, but ensconced within sheer blue cloth. It appears almost to be inside the safe bubble of a womb, yet it is lying outside of the mother’s skin. Something does not add up. This woman has no arms with which to carry her child, no head with which to smile at it. The baby is with its mother, but this mother is only a vessel for bringing life into the world, a vehicle, nothing more. Neither one can survive like this.

I put on my art-analytical hat. Bourgeois is exploring a certain helplessness, pointing to the interdependency between people, a circular quality, with a keen awareness that no one being is ever complete in itself. The mother gives birth to the child out of a desire to quench her need to care for another, and the child quite literally cannot live without the mother’s care. I find it interesting that Bourgeois herself was a mother but thought of herself more purely as a girl, stating that “The feminists took me as a role model, as a mother. It bothers me. I am not interested in being a mother. I am still a girl trying to understand myself” (qtd. in Searle). This headless mother seems to illustrate Bourgeois’s understanding that to be a mother does not make one a completed woman—and that no human is ever complete. We all depend on one another for meaning; even a mother depends on her child as a source of joy. Maybe this is why, even as grown women, we are always looking for a part of ourselves that will not mature. Is the recognition that one will always be—in some way—a girl the rite of passage to becoming a woman?

Of course, I know that hidden beneath this neutral analysis are my mother and I. Eating sent-backsteak, laughing. My analysis of Bourgeois’s artwork is only possible because my mother is buried beneath it, beneath the tangle of my pink, newborn words.

Like many people, my first encounter with Bourgeois’s work was with her giant spider, Maman, which she crafted out of steel in 1999 for the opening of the Tate Modern (Beaven). So popular was Maman that Bourgeois went on to create six additional bronze casts (Beaven). The one, however, that thrills me so stands before the Guggenheim Bilboa Museoa, the height of a small house. At over thirty feet tall, Maman is startlingly huge. You can walk between her legs and stare up into her giant underbelly.

Bourgeois’s creation of the series Maman came late in her career—she was already eighty-eight—but it has become perhaps her most famous work of art. Maman is aesthetically pleasing: mildly alarming, but beautiful in her horror. The notion that a predator this powerful is supported by such delicate legs is perplexing, and makes the spider appear that much more dangerous. That something so stealthy and predatory can be embodied in such a dainty package is jarring. People don’t trust her. There are numerous photos of Maman on the internet in which adults and children are seen running away, pretending that they are about to be snatched and devoured. Maman belongs to the schlocky universe of children’s and teenage horror, of Honey I Shrunk the Kids, The Incredible Shrinking Man, Arachnophobia, Tarantula.

Maman travels (Beaven). In Canada, the United Kingdom, Spain, most people who pose before her, ice-cream in hand, don’t think twice about her innate horror. They don’t necessarily know that “Maman” means “Mommy” in French. But for Bourgeois, Maman epitomizes the beauty and strength of motherhood. “’The spider,’” she once said, “’is a repairer. If you bash into the web of a spider, she doesn’t get mad. She weaves and repairs it’” (qtd. in Searle). A repairer. With this in mind, I suddenly notice the steel chain net hanging below her torso—the skin of her egg sack. We start to imagine the baby spiders nestled inside.

The 2008 documentary, Louise Bourgeois: The Spider, the Mistress, and the Tangerine, strives to make sense of her work in the context of her life. It contains numerous interviews, in which her interrogators try to bait Bourgeois into revealing some concrete meaning of her art, into comfortably categorizing her work as serving one specific purpose, highlighting one social or political pattern. But her responses are always confounding. Bourgeois puts everything in terms of emotion, explaining that, “The purpose of the pieces is to express emotion. My emotions are inappropriate to my size. My emotions are my demons” (The Spider, the Mistress). Not satisfied by the answers expressed by Bourgeois herself, the filmmakers turn to her childhood.

When she was a girl, Bourgeois’s father brought a nanny home to be his live-in mistress. His affair was a betrayal, but one that Bourgeois’s mother came to tolerate. Her father dominated the household, exerting his control over her and her mother through regular acts of humiliation, making them, in Bourgeois’s own words, a “’captive audience’” (qtd. in Kifner). According to the documentary, this emotional wounding influenced Bourgeois’s work until the day she died. Her art is rife with anger and violence. In her 1974 sculpture, Destruction of the Father, I see a fresh crime scene in which the children have murdered—and have begun to devour—their father. The symbolism is so explicit that I cannot help interpret the piece as a coping mechanism of some kind, an externalization and expulsion of emotions that would otherwise corrode Bourgeois from the inside. Her art seems a means of survival, a way to express savage fantasies that, in turn, offer her the intellectual ability to counteract any emotional trauma. She is dependent upon her art, and her art depends upon the drama of her inner turmoil for existence.

*

Caring, too, is a circular process. I know that we all know this. A child is born dependent on its mother; when its mother grows old and her body begins to weaken, the child cares for her in turn. There is a cross-stitching of care that occurs: we mend and we are mended. But because of my mother’s addiction, I became a mother to her when I was thirteen years old. Yet as she healed, regained her footing, I found myself losing my own—reverting, reversing, undoing.

*

And so the wounds necessitates the repairs. I suspect it is Bourgeois’s fascination with the innate female ability to repair whatever may come—her ability to endure, her strength, her power—that stoked her creativity. Where we see an intimidating spider, she saw a web—an improvised creation, a testament to its creator’s ability to sway and shift, to repair what has been damaged.

There are echoes of this toughness everywhere. Bourgeois’s 1952 sculpture Spiral Woman resembles the body of a woman being wrung out like a wet towel. Like The Woven Child, Spiral Woman also features heavy stitching. In both, Bourgeois indicates the female’s ability to withstand great pain, even torture; using the wounds of yesterday as grounds for new creation, restructuring the aches of the past into the fruit of the future, stitching them together in order to rebuild. With The Woven Child, Bourgeois suggests the female’s ability to transform her own body in order bring a life into the world. Women are literally and figuratively torn apart by the birth of that child—but they are able to come back together. They are the same person, though forever changed by the experience. There is nothing a little stitching cannot fix. A little web glue.

*

I finally left home at twenty-eight years old. I am almost ten years older than my classmates, yet I have entered college as if I were fresh out of high school. I still feel an eighteen year old’s need for my mother’s support; I call every day to tell her about class, to seek her advice and approval. I thought this dynamic had died with my role as a midwife, aiding my mother’s rebirth into the world of sobriety. But moving to New York, experiencing my first real separation from my mother, has pulled me back into this cycle. My mother looked older when I came home for Christmas. There was more grey in her hair, proof of the passage of time closing in and picking up speed in my absence. I felt that I had missed something. Bourgeois’s emphasis on the mother-child relationship disturbs and overwhelms me in a way that could keep me thinking for a long time. The rest of my life, perhaps. Long enough for the grey to touch my own hair.

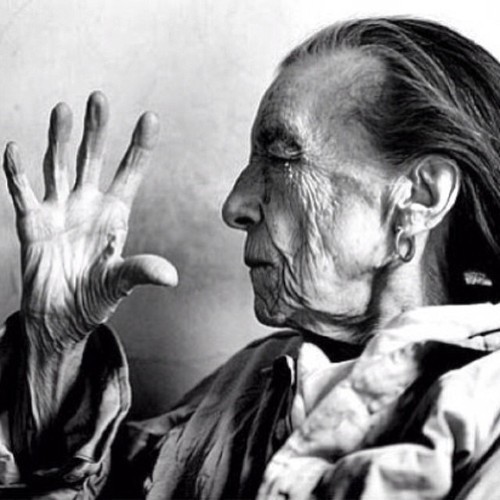

I found a portrait of Bourgeois online, a black and white photograph taken by renowned photographer Annie Leibovitz. Bourgeois is shown in profile. She is in her later years; her skin is weathered. Her hair is flung behind her neck in thick black and grey ropes, pushed out of the way for efficiency, speed, sight. Her palm is outstretched to the camera, as if waiting to receive a baseball—or the world. It is her palm that catches my attention: the leathery skin, the frail wrist holding up that too-strong hand—more powerful than a catcher’s mitt—fingers outstretched and ready to hook themselves around life, capture it in tangible forms. She winces ever so slightly, but the hand is steady. Fierce. All-knowing. I begin to understand that her sculptures have been shaping her—hands, psyche, heart, and mind—as much or more than she has been shaping them. These hands themselves are a work of art, this skin a roadmap of scratches and scars earned through hours wielding sharp tools, molding iron, clay, stone, cloth into forms. The grooves in her hands tell the story of her life; they are the riverbeds through which emotion has flowed again and again. These hands give her monsters a way out. They are perhaps her greatest piece of art, her highest achievement. I am unsurprised, then, that Bourgeois once proclaimed, “I am not what I am. I am what I do with my hands” (Art:21 24).

*

The Woven Child caused in me an emotional car accident; by chance, the piece found me when I was coming off a dream that had unearthed the cold reality I often push from my mind—my mother will someday die. Bourgeois—the work, the woman, the artist—forced me to consider that perhaps the female is simply a vehicle for new life, human or otherwise. This collision of life and art pricked me in a way that made me feel simultaneously intensely alive, deeply alone, and utterly fearful—human. My connection to Bourgeois’s work can only be described as what French philosopher Roland Barthes calls “punctum”: “that accident which pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant to me” (27). It is a violent attack of emotion; it is thoroughly individual—that which evokes punctum for me will not necessarily do so for you. Punctum is reserved for the work that affects us, often for reasons beyond verbal explanation. It affects us on a visceral level, unearthing something that can be neither denied nor explained. We are let in on a human secret that we may not even understand, but that we can feel permeating our bones. Bourgeois’s work is loaded with her emotional aches, aches profoundly different to any I have felt, but she exposes herself—her wounds—so completely that I cannot keep my own wounds from fusion with hers. This, to me, is the power of punctum at work.

*

When I encountered The Woven Child, scenes from my nightmare rattled through me. What I felt with sudden certainty was an understanding that my bond with the body that birthed me into this world will not last eternally. At least, not on earth. It is a bittersweet truth for all of us fortunate enough to have experienced such a bond. I am aware that this bond between my mother and me—between any mother and child—could theoretically be passed down to my own children one day. I am equally aware that the life I have chosen—a life in the arts, a life on stage, traveling in a constant state of selfish self-discovery—may offer no place for children. The thought stirs great panic within me, heartbreak even, given this new wave of understanding. My contact with The Woven Child has opened a wound of which I had previously been willfully ignorant: I am deeply troubled by the possibility of this chain of DNA dying with me. As I watch many of my friends beginning to have children, I cannot help but recognize in them what they may not: a primal sense of the maternal bond’s slackening as their mothers age, and an intuitive desire to recreate it by becoming mothers themselves.

In all of this I recognize my own fear of growing up, of no longer being my mother’s little girl: the idea that having my own baby would cancel out my ability to be my mother’s baby. The Woven Child prompted me to think about the safety of the womb, the inability to protect a child from the world beyond, and the desire to climb back inside that warmth and safety. Who wouldn’t want to stay inside? The world is harsh and cold and bright and unprotected. And yet, and yet … it is beautiful and worthwhile. This is a constant conundrum for me; perhaps it springs from my need, shared with Bourgeois, to insist that I am, above all, still but a girl trying to understand myself. Or perhaps I feel that I have done enough: I have cared for others; I have been mother to my mother at times; I can repair; I can be a mother to myself, now. Perhaps it is my turn.

*

In Seven in Bed, we see the undeniable need that people have for one another. I’m beginning to understand that it is creation, maintenance, and destruction that keep our world spinning. Women, like Bourgeois’s spiders, create webs—made from the most delicate of substances, queerly beautiful, able to be restrung, reworked, repaired, but also able to ensnare things to be devoured. Perhaps what I and Bourgeois are actually searching for is a keen understanding of the duality that a woman must embody: the duality of these webs. I am learning that life is about repair, about growing through my art and through the people who hurt me, love me, leave me, challenge me, and need me. We are all continually birthing ourselves—life-giving does not have to include being a mother in the biological sense. I can be that spider, that continually creating creature who is power and might in a dainty package. I have the right to be the intense female, the lost little girl searching for self-understanding, a mother, a lover, a seeker, and most of all, a human.

Works Cited

Art:21 Education Advisory Council. “Identity.” Art:21: Educator’s Guide to the 2001 Season. Stockbridge, MA: Toby Levine Communications, 2001. 20-25. PDF file.

Barthes, Roland. “Studium and Punctum.” Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Trans. Richard Howard. New York: Hill and Wang, 1982. 25-27. Print.

Beaven, Kirstie. “Louise Bourgeois: Maman Work of the Week, 1 June 2010.” Tate Blog, 2 June 2010. Web. 11 June 2014.

Bourgeois, Louise. Destruction of the Father. 1974. Plaster, latex, wood, fabric, and red light. Cheim & Read, New York. The Guardian. Web. 11 June 2014.

—. Maman. 1999, cast 2001. Bronze, marble, and stainless steel. Guggenheim Bilbao Museoa, Bilbao. Guggenheim. 11 June 2014.

—. Seven in Bed. 2001. Fabric, stainless steel, glass, and wood. Hauser & Worth, New York. Hauser & Wirth. Web. 10 June 2014.

—. Spiral Woman.2003. Fabric. Cheim & Read, New York. Circa Art Magazine. Web. 11 June 2014.

—.The Woven Child. 2002. Fabric, wood, glass, and steel. Worcester Art Museum, Worcester. Worcester Art Museum. Web. 10 June 2014.

Kifner, John. “PUBLIC LIVES; Portrait of the Artist as a Giant Spider’s Daughter.” New York Times, 26 June 2001. Web. 11 June 2014.

Leibovitz, Annie. Louise Bourgeois, New York, 1997. 1997. Photograph. Artnet. Web. 10 June 2014.

Louise Bourgeois: The Spider, the Mistress and the Tangerine. Dir. Marion Cajori and Amei Wallach. Zeitgeist, 2008. DVD.

Searle, Adrian. “Louise Bourgeois: a web of emotions.” The Guardian, 1 June 2010. Web. 11 June 2014.

Comments